Preface

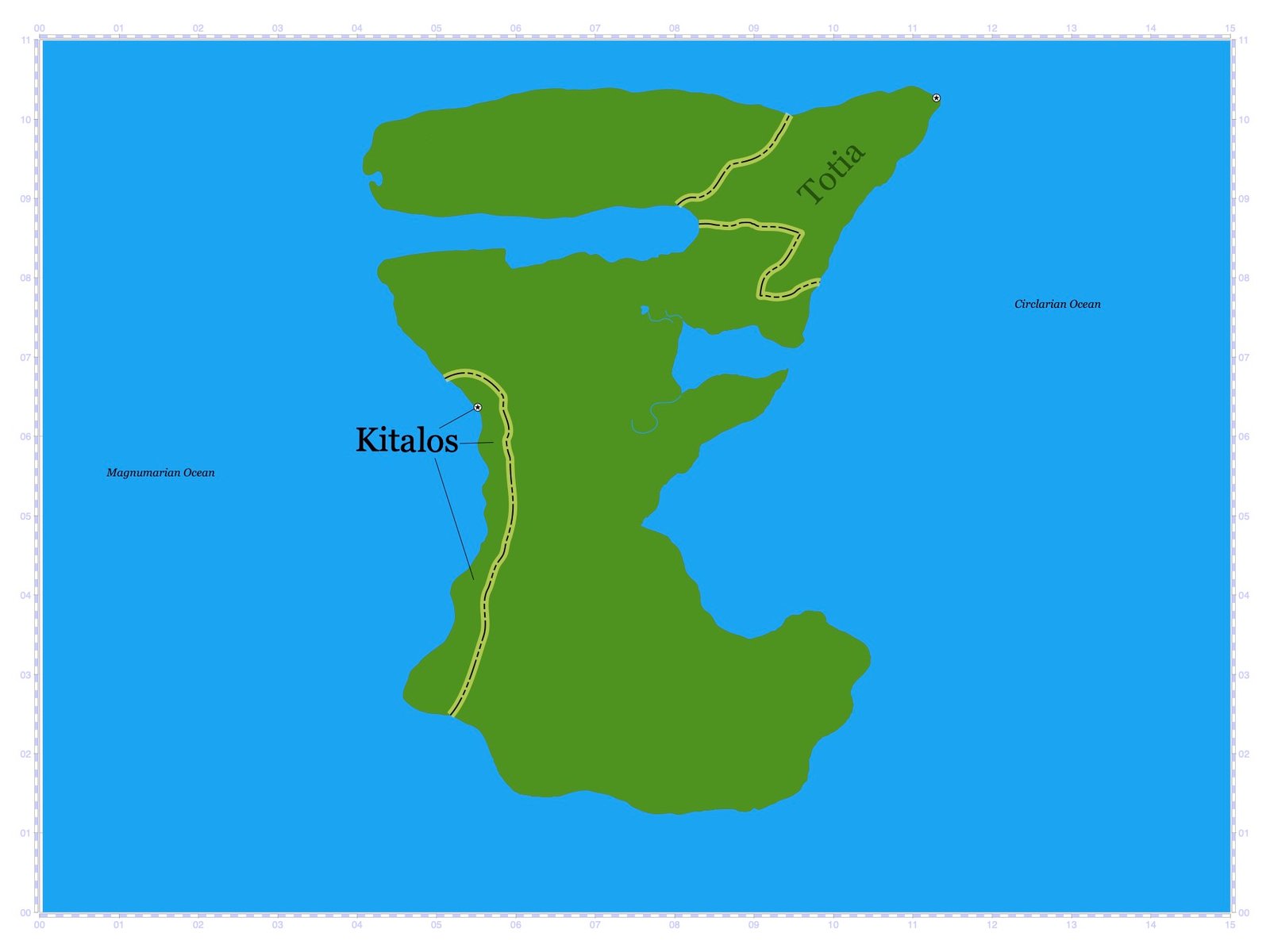

Within the span of about five to ten years, large numbers of people from Kitalos and Totia began to settle further into Remikra's interior. While the Totians did so by force, the Kitalans used mostly trade and diplomacy. In this era, both entities stayed within a few hundred miles of the coastlines, as the rate of territorial expansion made travel by ship the fastest route of navigation.

Totia

The desire to expand West, for many Totians, was countered by the presence of black moorwolves, a now-extinct species of wolf known for being extremely aggressive and territorial, as well as being larger than other wolf races. Meanwhile, the Totians expanded down the East Coast of Remikra, claiming land in present-day Combria and Ereautea.

The land in present-day Combria and Ereautea was more desirable, as the climate was slightly warmer, while the soil was fertile. Most important, however, was the presence of valuable minerals. They came to the St. Eschel River, where, at its mouth, they erected a temple (present-day Fort Braddock) in honour of an unnamed deity of "water and bountiful fruit." It was here that a priest made shale into an unusual precious and fragile material and carved it into a perfect human face, delivering it Chief Commander Atairus. This object became known as the Ark of Totia.

As they expanded South into present-day Combria, the Totians encountered an unfamiliar landscape. First, the climate was noticeably different, more temperate than the arctic atmosphere of their homeland. It was in Combria that the pine trees were fewer in number, and were replaced by seasonal deciduous trees as well as grassy knolls. Furthermore, the mountains were lower, with only a few of them being topped with snow during the cold months.

The area making up present-day Jestopole was occupied by the Mundaes, a nomadic group who had settled the area for its plentiful food sources. Their fighting legions were aggressive and defensive, and attacked the first Totian scouting party with no mercy. However, Totian reinforcements quickly defeated them. Two other groups, the Emorans and the Kusayes, who were allied to the Mundaes declared war on the Totians, leading to a three-year conflict. This ended in a stalemate, after which Totia and the two groups negotiated a land treaty, which allowed the nomads to settle the lands South of the St. Eschel River, under the protection of the Totians to the River's North.

Totia, despite being forceful, absorbed Emoran and Kusayean cultures. First, they gained colorful vocabulary describing the rediscovered plants and species in Combria. They also adapted the Emoran method of crafting stone figures of the faces of Divine beings; this was what inspired the making of the Ark of Totia in approximately 831 BCE. The Kusayeans, meanwhile, practiced the making of literary and spellfire inscriptions, with each item being made either of clay or within the earth. The scale of each item was deemed "larger than life," with each bearing great detail. Both the Emoran and Kusaye inspirations combined to bring about the art of building the stone statues for which the Totian Empire became known. But this absorption came with another change. When the Ark of Totia was delivered to him in 827 BCE, Head Commander Atairus granted the responsible Watchman, Krodus, succession to the Head Commander position for when the time would come of Atairus' death. This came as a withdrawal of promise to Alec, who had been previously given the same promise. Alec sought revenge by hiring an assassin, who succeeded in ending Atairus' life. In the three weeks that followed, Alec and Krodus, as well as their bands of Totian soldiers, fought within the streets of Totia. In the end, Alec won, and established himself to be a god-like ruler: an Emperor. While the law-and-order infrastructure retained the same shape, Emperor Alec wielded such power to govern over every aspect of Totian life, including religion, education, and artistic expression.

Alec established an Imperial Court of officials, standing superior to the Watch. The Imperial Court also had superior economic standing. Underneath the Imperial Court, the Emperor, and the remainder of the ruling class was an aristocracy class, followed by a class of landowners, workers, and "outcasts" (foreigners, criminals, or beggars). The landowners pursued a dream of reaping the benefits of the newly-found Combria region with the help of the workers, who were, via Imperial propaganda, coerced into pursuing a "dream" as well. When enough workers grew critical of the idea, Alec began sending slaves and prisoners to the new territory. With these people, labor often involved working in the crop fields or, later on, digging in the mines for precious metals. Meanwhile, crafters began constructing boats and carts as well as city buildings. These professions were slightly higher-paying, and resulted in the city of Totia expanding its jurisdiction to the mainland. However, such crafting was inferior in wealthy compensation to occupations such as a spell scroll librarian, a doctor, or an official for the Imperial Court. Within this society, trade began to develop, with indigenous nomad groups providing animals and fur for the Totians in exchange for valuable treasures, including quartz, which was discovered along the banks of the St. Eschel River.

Until this time, some Totians believed horses to be simply mythical creatures while others believed that they died out during the Ashen Years two centuries previously. The existence of horses was, in other words, a subject of speculation among Totians. However, during the first exploration of present-day Combria, the Totians were both horrified and amazed that their enemies, the Mundaes, were riding horses. Defeat for the Mundaes came when the Totians, with the help of their allies, developed assassin darts to eliminate key Mundae targets; but the Totians, having keen interest, began taking these horses for their own. Much to the skepticism of the leadership in Totia, Watch Officers and their soldiers boasted about having such creatures. The delivery of the Ark of Totia, however, came via a messenger on a horse, as he rode it into Totia for proof. From that point on, horses were considered highly-valued prized possessions.

In the regions of present-day Combria and Ereautea, it was much easier to grow large amounts of wheat and barley. Half of the yields of each land owner was taxed by Emperor Alec and commanded to be sent North to Totia. Thus, Totia saw nearly an oversupply of food. Much of this was also distributed to the surrounding Northern territories, allowing for the Totian Empire to begin its path to prosperity. Totians also rediscovered more sources of fresh water, most notably from the Taup River and Lake Relion between present-day Jestopole and Terredon, and also from the St. Eschel River. With more land came more trees, which provided plenty of burning fuel. All of these resources were harvested by those in slavery and indentured servitude composed mostly of the Mundae, Kusaye, and Emoran nomadic groups who were defeated.

However, a well-compensated occupation that came into existence was the Imperial message carrier. Carrying either scrolls or parchment, a carrier would usually ride from one place to another to deliver messages between two parties, most notably between the Imperial Offices and the regional Watch Offices. Early on, carriers would walk these distances; but later on, they used horses to spread communication in a quicker fashion. Both Totian cantons and towns out in the Northern and Combrian lands each had a center for conveying news to the local inhabitants, either in the form of large bulletins or pedestals for speakers. Between Totia and these towns, roads were not built, but rather formed by beaten-down paths made by common traffic. Eventually, wooden signs were made to indicate the direction and distance of certain places relative to the traveler's position. Totians were also known for making some of Remikra's first maps, using notable landmarks as guideposts. The most common mode of transportation was walking. However, people also used mule-driven carts, Totian ships along the coast, and, for those who were wealthy enough, horses.

As more outposts were established, there was a rise in demand for infantry soldiers. Watch Officers gave military opportunities to criminals and defeated nomadic prisoners of war to join the ranks of the Totian Army, with special checks and balances to prevent these people from uniting in mutiny against the Totians. This strategy was very successful, allowing the Empire to increase in size; and such a system inspired the idea of "becoming a citizen" in countries that would exist later on. Many nomadic groups began navigating on ships for trade, forming some of the first post-Ashen sea merchant guilds. Some of these groups turned hostile toward the Totians, prompting Emperor Alec to expand the Totian Navy. Those who fought alongside the Totians were the Kusaye and Emoran groups, who became allies after diplomacy deals following their defeat. However, the Fundae and Mundae groups remained hostile, while some factions from within these entities broke off to remain neutral from the situation.

Small libraries for spellfire scrolls began to crop up in the larger Totian outposts as they grew, with a trained librarian managing each. Indigenous nomads added to the spellfire vocabulary as scribes copied contributions to an ever-increasing archive of scrolls. Although in practice since before the Ashen Years, it was during this time that warriors sought more frequently to these scribes and librarians to enhance their weapons. For example, a library-influenced enhancement of the Totian bow-and-arrow to strike targets from further distances was believed to have initially been the tactic to help defeat the Mundaes on horseback.

Kitalos

Staying West of the Magnumarian Shield, Kitalan settlers moved down the West Coast, where they picked up a variety of exotic crops. Some, however, began exploring the highlands, where they cultivated Remikra's first potato crops.

Up to this point, most Kitalans lived in shacks made of either straw, mud, or mulch from a crop imported from the Northern boundary known as flaxweed. As they traveled down the coast, though, the Kitalan settlers discovered large deposits of white marble. They began carving out of these slabs, using the marble to build houses and other structures, as well as irrigation systems. As a result, the West Coast began to take on the white marble urban landscape that it bears today.

Kitalan explorers were keen to continue South, rather than North, along the coast of the Magnumarian Ocean for a variety of reasons. Along this region, the terrain and elevation remained mostly the same. However, the vegetation began to change drastically as they neared the tropics. Palm and coconut trees became more frequent along the beaches, while thick jungles sprung up inland, where hundreds, even thousands, of different plant and animal species were noted. According to unconfirmed accounts, there were, on occasion, observations of "leather birds" which closely resembled prehistoric lothars; such "leather birds," however, had they existed, went extinct not long after. Just like in the Kitalan capital to the North, there was a wet and dry season. However, the air, in general was more humid; and the heat was more intense. Sometimes, during the wet season, tropical cyclone systems would lash the coastline with relentless wind and rain.

Members of the Quitzdodal population were encountered here; and they began to mix with the Kitalans, giving the Kitalan ethnicity a more Southerly appearance. These groups had vocabulary for the variety of plants and animals that existed here, as well as the weather patterns. These people also believed in a unified spirit which existed in reality in the form of all living animals, with the souls of each rejoining the One Spirit after death before reincarnation. This, according to scholars today, was perhaps a partial inspiration to a lot of the existing monotheistic religions. Instruments of plant material from this region became included in the consorts of musicians who began journeying around Kitalan lands, especially in the North, which drew even more people to exploring the Southern regions. Stories and fables depicting trips into the jungle regions with plant and animal encounters were presented on large murals in the city of Kitalos; many of these murals can still be seen today. Such stories were also played out in theatrical settings. And it was during this time that Kitalos began sending out post-Ashen Remikra's first scientists, who observed these new exotic regions and added their notes to Kitalan libraries. As Kitalan territory expanded and the Kitalan population began to grow, so did the Kitalan Council and the number of local councils. In accordance to Kitalos' policies of openness, the Quitzdodal members were integrated into the system, with a lot of them attaining elected positions of power.

Such an attainment by the Quitzdodal led to advantages in the Kitalan democracy, as the head Council passed a measure in the Kitalan Moral Code to establish a base minimum compensation for all rural dwellers as well as lower-class people within the city. Along with the current economic system came a profession of merchants who would trade Quitzdodalan goods for wealth or services, as the Quitzdodal established a network chain of trade between Kitalos and the Southerly regions. By this time, the coins made of gold ore in the Magnumarian Shield became the dominant form of Kitalan currency. Olives, wheat, barley, and maize continued to dominate the Kitalan food market. Rainwater collected in the Southern jungles was transported back North via carts in exchange for goods from the North. Most importantly, however, was the discovery of a large clay bed on the Southernmost shoreline; such material was used in making bricks for the ever-expanding road network.

The Quitzadodals brought to Kitalan society the idea of placing reference messages on trees (i.e. telling someone to speak to another party at a certain time). This was adapted in the North by placing large wooden polls in the center of each town. These messages were not carved on, but were rather written in the form of a glowing paint made of spellfire crafting, which would later be washed off. Many of these polls were placed on the sides of Kitalan roads, which served as some of the first traffic signs in Remikran society. These became important as the road network began to expand and grow more complex. To help simplify the situation, the Kitalan Council passed measures to make the roads more consistent throughout the territory. For example, the clay material found in the Southernmost shoreline was the standard material used for the main routes to endure the constant traffic of walkers, soldiers, and animal-drawn carts.

Not all Quitzadodals were friendly to the Kitalans. When contact was first made between the two, half of the Quitzadodalan population separated and formed a hostile faction. The two halves fought one another frequently, with one of the halves being allied to the Kitalans. One disadvantage that the Kitalans encountered was that their eagles were not able to fly very well in the tropical regions, as they were accustomed to high elevations and wintry conditions. This made defense very difficult, considering, also, that the enemies hit their targets by "pea-shooting" poison darts from atop jungle trees. However, the Kitalans and their allies adapted by utilizing a discovery they made by the seaside: clam pearls producing the spellfire needed to conceal oneself. With this resource, they managed to strike the enemy treetop shooters and take over the treetops themselves.

An issue that arose with the "invisibility pearls" was that once the spellfire was spent in a given pearl, the spellfire was spent permanently. After years of experimentation, Kitalan librarians and spellfire scholars managed to obtain the inscriptions needed for the concealment spell.