Crisis in Layda

Disorder ensued in Layda in 775 BCE, as working-class uprisings began, led by the rebelling figure, Teschitarian. The local Legion was constantly dispatched to bring order to the city streets. But in December, 773 BCE, Teschitarian's forces united and massacred the Legion, killing many of the Totian soldiers, including the Legion General Maclarain.

Double-Crisis in Tecere

Meanwhile, similar issues were underway in the city of Tecere, located in the heart of the Remikran Plains. Beginning in 774 BCE poor farmers rebelled against the wealthy exploitation of the food supply. It was here as well that a local Legion was dispatched, with this one under command of General Armstus. But while Armstus struggled to maintain order in Tecere, he encountered an additional rivalry: Kovan. Kovan was a strong veteran soldier of the Legion, having served since ten years before Armstus joined in 777 BCE. Contemporaries described Kovan as having a "pushy" personality, causing him to be slightly disliked by the incumbent Legion General, Alexander. To appease Kovan, Alexander had repeatedly promised Kovan the Legion General position upon retirement; but in 774 BCE, when he finally retired, Alexander instead gave the General position to Armstus, who had shown unusual strength and talent in service. This sparked jealousy from Kovan, who subsequently left the Legion. He took advantage of the ongoing farmer rebellions and by 771 BCE made himself their leading figure, blaming Armstus for the poverty.

The Call from the Imperial Seat

In October 772 BCE, General Armstus received a letter from Emperor Kestaven to travel with several factions of his Legion to address the crisis in Layda. Armstus, however, responded with his concerns over the imbalance of power and order in Tecere. In the following April, Armstus received a response from Kestaven, in the form of a young man named Marcan, deemed by the Emperor as a "worthy General of temporary replacement," as well as numerous soldiers from the First Legion (Kestaven's strongest Legion). Furthermore, Kestaven promised Armstus a large sum of gold for success in Layda; and thus, Armstus obliged.

Arrival

In September 771 BCE, Armstus and his troops arrived in Layda where they immediately lay siege to the city. Such a maneuver lasted only until October, when Teschitarin's forces broke through and drove Armstus to the hillsides to the immediate Northeast a few miles away. While his soldiers held defensive positions there, Armstus alone ventured undetected into the city of Layda, where he examined masses of Laydans poor and starving. Baffled by the circumstances here, Armstus spent the next few weeks observing life in Layda and figured the reason for the worker uprisings: Emperor Kestavan had been exploiting most of their wealth and resources by having Legion soldiers cart or ship large portions of it to the city of Totia. In April 770 BCE, Armstus joined forces with Teschitarin as they agreed to side against Kestaven and form a separate Empire.

The Deal

Not long after this agreement, Armstus received a taunting letter from Kovan, saying that Marcan was dead and that he was now in power. Armstus responded with a letter asking Kovan to join him in breaking from Emperor Kestaven. In compensation, Kovan would share Imperial power with Armstus and Teschitarin in the form of a triumverate, where Kovan would rule from Tecere, Teschitarin would rule from Layda, and Armstus would rule from a third place to be later determined. Each member of the triumverate would have equal power and make decisions by a consensus vote. In December 770 BCE, Armstus received a letter of consent from Kovan.

The War in the West

In March 769 BCE, Legion troops from the East arrived to obtain more resources from Layda, but were driven away by Armstus' forces. And thus, the war began. In April 768 BCE, Kestaven responded with numerous forces sweeping the entire continent, almost to the doorstep of Layda itself. While victory seemed to be swift and easy for Kestaven, Kovan's reinforcements finally joined with those of Armstus; and by June 767 BCE, Kestaven was pushed back as far as the Northern boundary of present-day Combria. In September 766 BCE, Kestaven's forces launched an offensive, regaining territory Westward. It was in the city of Maern that Armstus and his Legion held ground; and Armstus determined for this city to be the third Imperial capital. Meanwhile, Kestaven held onto Eskant and the surrounding territories. This, however, was the end of any victorious gains for the East, for the war had been quite costly. Emperor Kestaven called for a meeting with Armstus, Kovan, and Teschitarin in the city of Eskant; and on the final day of September, they signed a peace treaty.

After the War

In January 765 BCE, Armstus heard a rumor (or perhaps created one) that Kovan and Teschitarin were conspiring to overthrow him. One month later, Armstus sent an assassin who successfully disposed of Kovan. In September, he arrived in Layda, where it is believed that he personally ended the life of Teschitarin. He then proclaimed himself the sole Emperor of the West, ruling from Layda.

West Totian Empire

Despite such acquisition of power, Armstus sought to establish a fair and prosperous Imperial society.

West Totian Empire: Geography and Climate

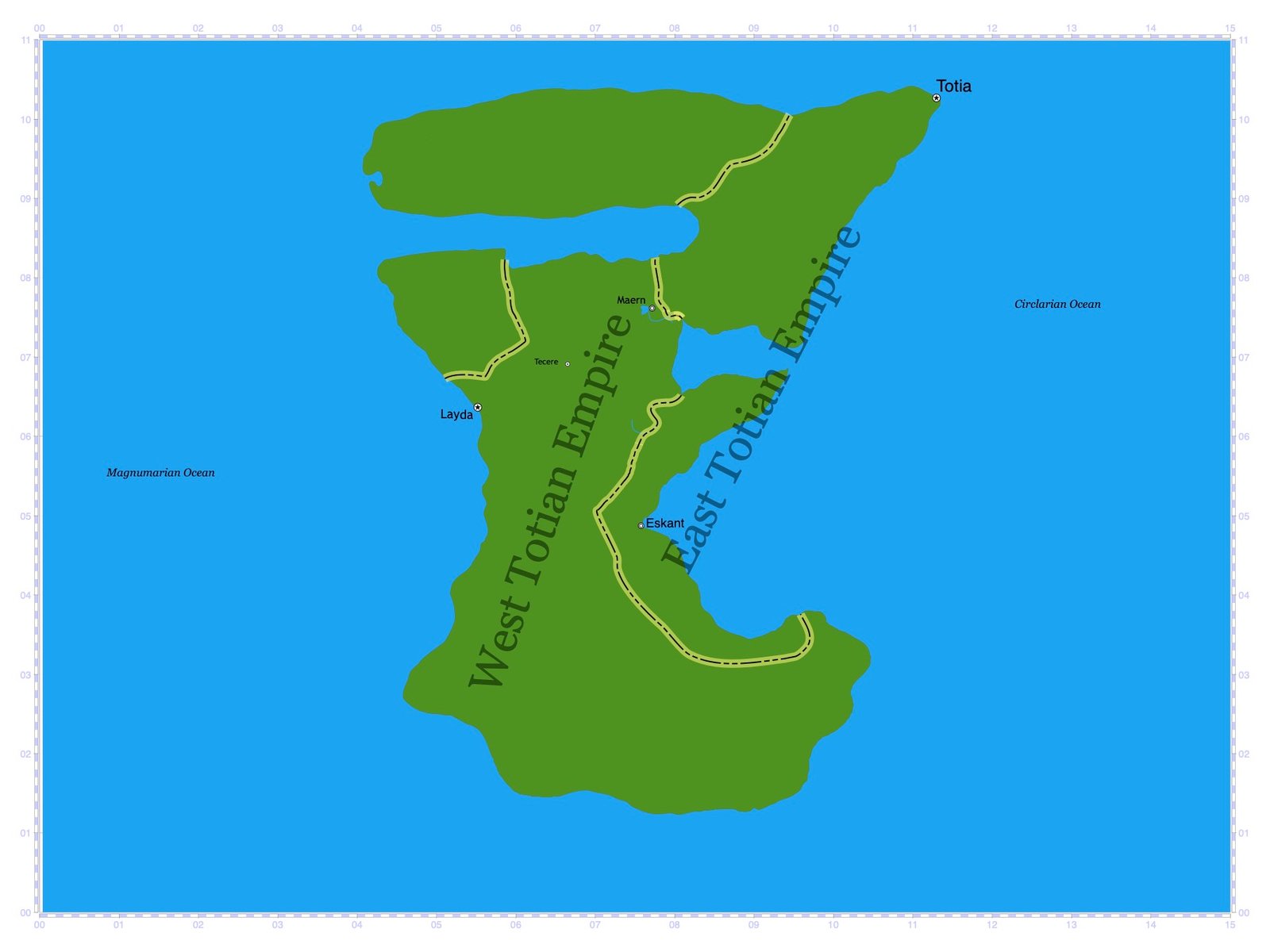

The West Totian Empire spanned the Plains, the Interior Desert, the Southern Coast, and the area surrounding Layda.

With lakes and mid-level mountains surrounding the city of Maern, most of the central Remikran Plains was flat, with its fields being turned into grain and flaxweed crops managed by farmers. Here, the seasons of winter, spring, summer, and autumn were well pronounced, with occasional storms cropping up in the spring and summer months. To the South, the Interior Desert contained mostly uninhabited ridges and salt flats, with most of the vegetation existing either in the form of cacti or small regions surrounding oases. Here, mild to hot temperatures were accompanied by little to no precipitation. Meanwhile, the Southern Coast contained low-lying territory with occasional rolling hills and deltas, as well as the Escarpments lining the desert region many miles inland. This area was thick with tropical vegetation, which benefitted from the wet-dry season alternations of a year-round tropical climate. Layda, in contrast, had a slightly drier climate, while the surrounding inland plain regions, surrounded by hills and low mountains, as well as small forests of local trees and large grasslands, enjoyed a warmer semi-arid climate with a mild wet season.

West Totian Empire: People and Society

Large portions of the West Totian population consisted of Quitzdodalan and Tahnish ethnicities, as well as a mixture of the two. Meanwhile a small population of East Totians existed. West Totian Vernacular developed in this time period as a distinct dialect, further removed than the East from the original Aerdn tongue, and inclusive of both Tahnish and Quitzdodalan vocabulary. Emperor Armstus allowed any and all different religious practices to be carried out by his people as he incorporated a doctrine of religious freedom. To show this, the Emperor displayed his unique belief: a Tahnish version of the original Totian Divine (the multiple Divine Spirits) with each being communicated with by soul gems, an invention of the Tahnish. Ideally, the collective Divine made the existence, technically, of one God. Despite his doctrine of freedom of religious expression, however, Emperor Armstus obligated his people to pay taxes to build Imperial Temples for such his belief, for Armstus still considered his religion the official one. Most were concerned, though, with the happenings of the regularly-occurring Desedic Tournament, which originated in Kitalan society in the early 700s BCE. Most of these tournaments were local and were discontinued after the defeat of Kitalos. They were reinstated by Emperor Armstus as the Arsteic Tournaments, to be held in a specific location once every four years. Also popular during this time was poetry; three of the most significant writers during this time were Maestor, Oram, and Kordam. There were also the stagemasters, who utilized such written material with music to create more sophisticated theatrical productions. Armstus also reinstated the Kitalan library system; however, there was a compromise in that only successful graduates of traditional Totian curricula could access these. Nevertheless, it was with this educational system that the practice of research became well-established. Pupils were made to receive permission to borrow books from institutional libraries in order to fulfill important assignments.

West Totian Empire: Government

The West Totian Empire had an Imperial top-down system like the East. However, Armstus also established elected representative councils, national and local, to advise the Imperial class on certain decisions. Justice court systems were also established. Although such bodies were elected, they had no direct power over the Imperial system. Armstus still had direct command over laws, decisions, and actions, which could be invoked or revoked at any time.

West Totian Empire: Economy and Resources

Like the East Totian Empire, the West established gold coins as standard currency. However, in contrast, Armstus taxed landowners and other members of the aristocracy. Revenue from this was used to pay public servants to carry out such projects as road construction and aqueduct maintenance. West Totians were also paid handsomely to fight in Legions. To prevent the economic inequality that eventually plagued early Kitalan society, Armstus enacted laws limiting how much merchants could charge for what they sold. Remarkable infrastructural achievements and a large middle-class population emerged from these policies. Such an era was also blessed with plentiful resources. The Plains provided grains, flaxweed, and beef, while the area surrounding Layda yielded olives. Exotic meats and plants came from the tropical Southern Coast, but were reserved mostly for the Imperial and aristocratic classes. West Totians of all classes enjoyed plentiful fresh water imported from the lakes near Maern, the Magnumarian Shield, and the Jo Reneed River, the latter of which was shared by the East Totian Empire. A widespread aqueduct system based off the works of Estrayon directed large amounts of fresh water to large metropolitan areas. Meanwhile, light and heat was generated mostly by wood and sometimes coal. Quartz continued to hold high value, as the Quartz Trail had survived the war and the ensuing chaos of the years before. Gold was plenty as well. In fact, for a number of years, the value of gold decreased in the West. Despite such economic growth, Armstus still retained the policy of forcing criminals and enemies into involuntary labor; although that was kept to a minimum while paid labor dominated the system.

West Totian Empire: Communication and Transportation

The invention of the envelope in the 760s BCE allowed for more convenience and privacy in the transit of messages, especially important ones. Eagles became increasingly used to spread these messages. Meanwhile, a consistent press system of pamphlets was run by the Imperial class while other journals existed locally. Roads to all major cities were either paved or bricked while only small villages were connected by gravel paths.

West Totian Empire: Defense and Fortification

The Totian Empire of the West prided itself in strengthened numbers of its Legion members. Navy ports were also established along the West, South, and North coastlines, while the treaty signed with the East kept ports from both Empires a certain distance from the border. The West Totian Empire also established a fleet of eagle-riding soldiers. Although the early Kitalans had such assets, Armstus was the first to have an entire Legion dedicated solely to flying. Utilizing spellfire, these flyers demonstrated their power by extinguishing an attempted invasion against a local village in 764 BCE. With such forces in place, Armstus maintained the peace treaty with Kestaven, while maintaining peace and neutrality with the independent Quitzdodalan and Tahnish factions at sea. The biggest concern for Layda was the Lynds; but they were effectively kept at bay in the Pimdanian region.

West Totian Empire: Spellfire

As mentioned earlier, soul gems were invented by the Tahnish, and were used in acts of "divine intervention" in the West Totian temples. They were also used as part of scare tactics against enemies on the battlefield. Meanwhile, the Layda Citadel Library was established in 763 BCE, where scrolls were organized in "files." One year earlier, in 762 BCE, the Library of the High Lake, similar to the Citadel Library in Layda, was established in Maern, where scholars copied and edited scrolls to enhance spellfire practices.

East Totian Empire

The East Totian Empire, as it became known after the war, encountered a very serious problem: the divide between the Northerly and Southerly regions by the Inland Sea. The coastline in between, after all, was under control of the West Totian Empire.

Estrayon, during the war, had fled the Plains, not wanting to heed to the battle call of his friend, Tor. Estrayon arrived in the city of Totia, where he began to study in the Citadel Library. It was here that he refined his practice of spellfire to a science, establishing the Estrayon System of Spellfire Measurement. Impressed by his talent, Emperor Kestaven employed Estrayon to engineer a "perfect system" for the flow of economic resources throughout the East Totian Empire. However, controversy arose when Estrayon discovered that not only was an unfair amount of wealth flowing to the Imperial class, but also that the "perfect system" Kestaven was calling for would worsen such inequality. Estrayon, instead, began to direct popular dissent toward the Imperial establishment, leading Kestaven to sway Estrayon with a large payment and relocate him to the city of Eskant, where he could govern the Southerly portion of the Empire. To this, Estrayon obliged seemingly; and Kestaven saw this as a solution to keeping power over the region.

East Totian Empire: Geography and Climate

Near the city of Totia, the terrain was mountainous and covered with pine trees and grasslands. The weather here included a fairly large amount of precipitation, and alternated between frigid winters and mild summers. Combria had slightly lower mountains where the pine trees alternated with deciduous trees and larger areas of grass. Here, the summers were warmer and winters less cold. Across the St. Eschel River, the mountains turned to rolling hills while deciduous trees and grasslands dominated the landscape. Even warm summers and milder winters came here, although there were occasional storms from the Inland Sea. In the Chemkan region, tall ridges were accompanied by coastal and interior lowlands, where grasses, warmer-climate trees, and crops like cotton prevailed. Hot summers and mild winters brought about occasional tropical rainstorms. South of the city of Eskant lay the flatter lands sloping to a low-lying ridge bordering the Interior Desert. Palm trees and tropical vegetation dominated the area near the coast, where an alternating wet-and-dry season delivered yet more tropical storms, while aridness and no vegetation dominated the desert region, most of which under West Totian rule.

East Totian Empire: Society and Government

Distinct Totian Vernacular dialects developed across the East. Near the Imperial capital, Fundae vocabulary dominated such changes. In the region Combria, Mundae, Emoran, Kusaye, and Camaran speech items prevailed. In present-day Ereautea emerged Camaran dialects, as well as traces of Lyndan. Camaran, Chemkan, Tahnish, and traces of Quitzdodalan were integrated into the Totian Vernacular in the Chemkan region, while Tahnish and Quitzdodalan existed South of Eskant. It is interesting to note that, since Camaran dialect bases were present between the North and South regions of the Empire, Camarans were often hired as translators and interpreters to help resolve communication barriers. Kestaven's policies on religion continued after the war, where those who practiced different beliefs still had to respect Kestaven's monotheistic beliefs as "genuine." Although the East absorbed Arsteic athletic sportsmanship, Kestaven still propagated death arenas for some criminals and enemies of the state. Reflecting politics surrounding the war, musical and theatrical productions continued to portray Kestaven as a protagonist against the "corrupt" West. East Totia's traditional school system reinforced such beliefs. In contrast to the West, the Imperial top-down model in the East contained no elements of democracy. In the North region, order seemed to be kept. However, in the South, Legion generals, far removed in distance from the Imperial capital, began rivaling each other for power. This was what led Emperor Kestaven to send Estrayon to rule the South as "governor-general" from Eskant.

East Totian Empire: Economy and Resources

The economy in the East Totian Empire entered a downward spiral as the merchant class began shrinking while a beggar class began to emerge. Unlike the West, laborers here were not paid very well; and, in fact, they began seeing copper in payment instead of gold. Meanwhile, the aristocratic and Imperial classes were shrinking in number, but the wealth of both was growing. Despite such problems, the Northeast region near the city of Totia continued to produce gold and wood while Combria produced wood and grains. Meanwhile, present-day Ereautea produced wood, grains, and fruit. The lands North of Eskant produced cotton and flaxweed while the lands South of Eskant produced glass and sandstone, as well as traded tropical plants and animals. The main regions from which originated food were the Combria, Ereautea, and Chemkan regions. Lakes from the North, Combria, Ereautea, and the Chemkan region, as well as oases in the desert regions provided plenty of fresh water. Wood from Combria, Ereautea, and the North provided for heat and lighting for most East Totians, while gold from the North and quartz from the St. Eschel River region were items of valuable trade. Families of forced labor continued to exist, being occasionally split by Totian officials; and temporary involuntary labor continued to be used as criminal punishment. Unlike the West, though, such labor was becoming increasingly popular, while paid labor was yielding less compensation. Emperor Kestaven worsened the situation by passing laws that ultimately forced more people into involuntary labor.

East Totian Empire: Communication and Resources

The East absorbed the Western invention of the envelope as a way to carry messages. The East Totian Empire, however, is credited with the idea of developing upon the Kitalan light tower communication idea, by utilizing a more uniform system of color-coding to spread simple messages. Meanwhile, one long road was constructed extending from the Imperial capital through the Northeast, along Circlarian and Inland Sea coastlines, and down to the Chemkan region, where it split to travel along each side of the Chemkan Ridges before meeting again in Eskant. One noted inconvenience was that such a road passed through the West Totian Empire, where travelers had to either pay a high toll or take a ship across the Inland Sea. Aside from that, this main road was lined with bricks while lesser roads contained either dirt or gravel. As regional domestic travel animals were continually used, eagles were introduced to the Northeast.

East Totian Empire: Imperial Defense

Despite being reduced to less than half in number, the East Totian Imperial Legions and Navy were still surprisingly strong, with the latter taking by surprise Fundae pirates, who were attacking the city of Eskant in 762 BCE. The most significant development, however, was the completed causeway system around Totia proper. Initially it consisted solely of linked ships. However, an idea drafted for rafts fixed to poles rooted at the bottom of the Bay where the rafts opened and closed for defensive and commercial purposes was proposed in 779 BCE. It was finally approved by Emperor Kestaven in 776 BCE; and construction began the following year. The project was completed in 761 BCE, when Kestaven personally crossed one of these to lay a wreath on a memorial dedicated to the first battle with the Fundaes on the mainland.

East Totian Empire: Diplomacy

The treaty signed with the West Totian Empire in 766 BCE drew a border between the two Empires. A partial military alliance existed where each Empire could send to the other, for a high payment, a limited number of mercenaries, provided that the entity with which the receiving Empire was engaged in conflict was not in ally to the other Empire. Goods were traded between the two Empires, but each Empire charged a tariff for each good. This led to a "tariff war" in the late 760s BCE. Most land factions of the main nomadic groups were friendly to the East Totian Empire. The ones at sea were mostly neutral; however, the ones further East on the Circlarian Ocean were hostile.

East Totian Empire: Spellfire

The original Citadel Library in the city of Totia copied the "file organization" method established in Layda. Although, the Estrayon System of Spellfire Measurement became commonplace among spellcrafters of both the East and West. In 762 BCE, Estrayon established his own Citadel Library in Eskant. This was met with contempt from Emperor Kestaven, who demanded for it to be closed down. Instead of doing that, in 761 BCE, Estrayon moved the Library to a hidden location further North in the Chemkan Ridges. Today, that institution is Tandowyn University.